Predictive analytics tools are boosting graduation rates and ROI, say university officials

University enrollment officials say that predictive analytics is not only improving student graduation rates but also bolstering their institutions’ bottom lines.

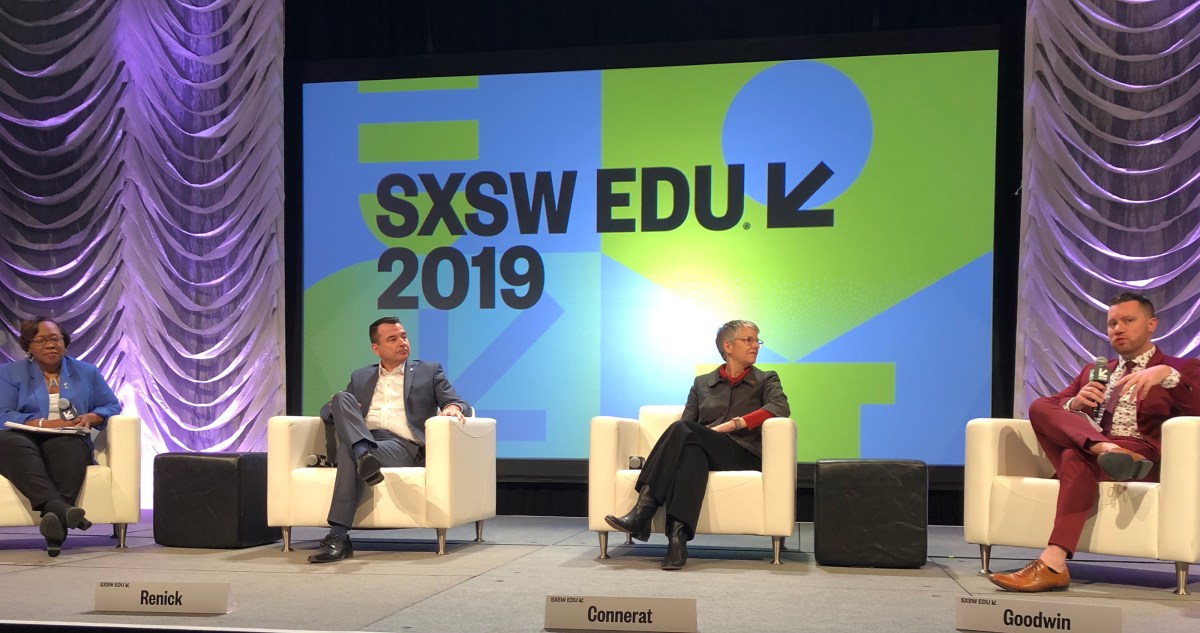

The use of data analytics tools to identify students at risk hasn’t always been an easy sell with faculty and advisers, administrators from four universities said Tuesday at the South by Southwest EDU 2019 conference in Austin, Texas. But thanks to improved data dashboards, more timely reporting and greater commitments to training, institutions are developing new approaches to mitigate factors that contribute to student dropout rates and intervening to help struggling students faster.

Carolyn Connerat, associate vice provost of enrollment management at The University of Texas at Austin, was among those who said predictive analytics is making a difference. Since 2013, when the university began embracing data analytics tools to better understand how well students were adapting to the rigors of college, graduation rates have risen from 53 percent to nearly 70 percent, she said.

Gains in graduation rates have also translated into enrollment increases as more seats become available to accommodate new students, without having to expand facilities, she said. “When we started the [predictive analytics] initiative, we were enrolling around 7,200 freshmen a year. Now, we’re enrolling close to 8,000 a year,” Connerat said.

At Georgia State University, Timothy Renick, senior vice president for enrollment management and student success, attributed “75 percent of our growth and student retention rates” to the use of predictive analytics.

Renick said GSU has raised its graduation rate by seven percentage points, and even more for lower-income students. He noted that about 60 percent of GSU’s 51,000 students qualify for low-income Pell Grants.

“If you can hold onto students who otherwise are walking away in mass, you’re helping … the fiscal foundation of the institution,” he said. Renick calculated that a 1 percent improvement in retention at GSU translates into a $3 million benefit for the university.

All the difference

Renick said GSU tracks 800 academic risk factors and that 98 percent of those are the same as what the university was tracking previously. The difference now is “we’re letting students know too, and sooner,” he said. One outcome of the analytics, for instance, was a decision to buy each academic adviser a second computer monitor so students could follow their conversations more easily.

Before instituting data analytics disciplines, “We never had the understanding of students struggling early on in the semester and how we can avoid leaving a third of students behind,” he said.

At the University of Central Florida, predictive analytics helped administrators figure out why students in one residence hall year after year had a harder time graduating than students elsewhere on campus. It wasn’t because of more parties, said Ryan Goodwin, director for higher education innovation at UCF.

That residence hall offered the least expensive housing on campus, but also tended to fill up with mostly last-minute enrollees, data showed. Goodwin noted that for every student who drops out for academic reasons, five drop out for financial reasons.

“So that signaled we needed to provide something different in that residence hall. Without analytics, we would have missed the struggle,” he said.

The university also added 16 financial risk factors to its system and worked to sensitize academic advisers to stay alert to financial struggles.

The next level

Analytics also helped administrators identify “toxic pairings” — difficult classes that when taken concurrently tend to cause UCF’s 68,000 students to struggle more than usual.

Insights from analyzing data patterns have also spurred a variety of intervention programs. UT Austin, for instance, developed a program called “Major Switch.” Data analytics helped university faculty and advisers identify students struggling in STEM fields within the first six weeks of classes and alert them that they still had the option to switch majors, Connerat said.

Ninety-five percent of students who opted to switch majors in those circumstances have gone on to successfully complete their studies, compared to 50 percent of struggling students who stuck it out, she said.

Analytics has helped enrollment executives make a stronger case to leadership for more funding for advising support for students, said DeAngela Burns-Wallace, vice provost for undergraduate studies at The University of Kansas. She said it’s also boosted buy-in with faculty by showing them how students are progressing through their curricula.

That’s important, she said, because if faculty members are slow to enter grades, it takes longer to identify students who are struggling. It’s also important, she said, because it gives advisers more time, training and capacity “to bring conversations to the next level.”

To continue following EdScoop’s coverage of SXSW EDU 2019, read about how states are overcoming challenges with early childhood education data through a national collaboration network.