For virtual reality to stick, universities need meaningful classroom content

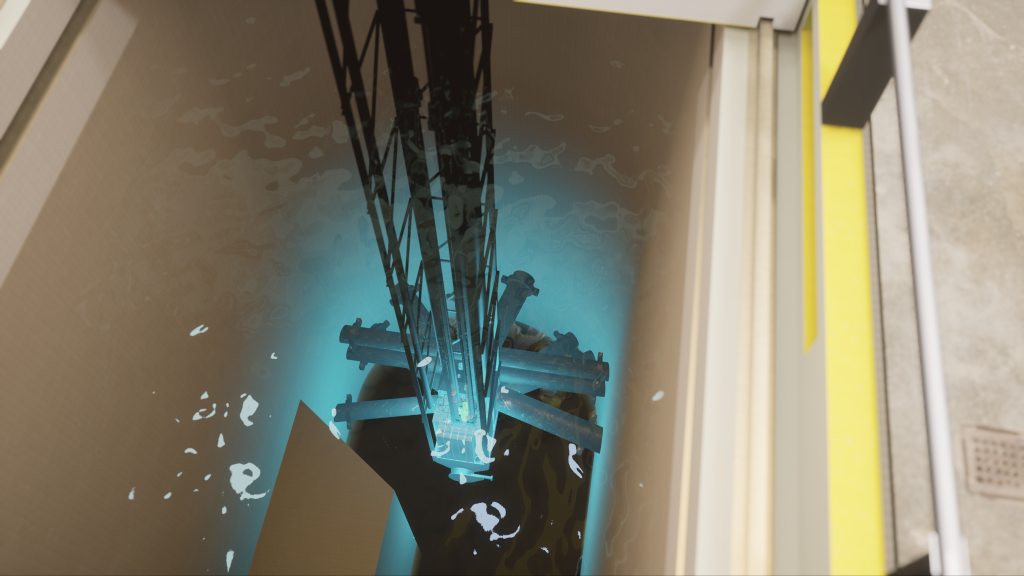

All that’s required to explore the decommissioned Ford Nuclear Reactor at the University of Michigan is a virtual-reality headset and two handheld controllers.

Once “inside,” you can walk around and explore rooms or casually drop yourself into the pool of water that surrounds the reactor’s core for a better look, or run an experiment placing a piece of iron wire inside the chamber.

With some headsets becoming more affordable, dropping to below $500, augmented- and virtual-reality lessons are becoming more common and more accessible on college campuses nationwide. But even as it becomes theoretically easier for faculty and administrators to bring VR into classrooms, there are still financial and technical hurdles before it becomes mainstream.

“We could go buy a bunch of headsets and try to get them to folks, but if we don’t have good content to run on them, that wouldn’t be a good use of the technology,” said Jeremy Nelson, who leads Michigan’s extended reality initiative. “It’s not one of these, ‘if you buy it, they will come’ type of things.”

Building a VR curriculum takes more than just buying some headsets and downloading a program. To scale, it takes teams of instructional designers, multimedia producers and software engineers — working with the same graphics engines used to build video games — to develop experiences that achieve specific learning objectives or fully immerse students in a digital environment.

But the result of these efforts is that more students are gaining access to learning environments that offer previously inaccessible experiences, like consequence-free nuclear tinkering, or a human cadaver with all the body parts labeled.

And as more cutting-edge universities dedicate time and resources to extended reality, others will likely inch forward, said Mark McCormack, Educause’s senior director for analytics and research.

“That’s more of a reaction to something that’s becoming more normal and more generally, what students and staff and other stakeholders are going to expect and demand as part of their technology experiences in higher ed,” he said.

Slipping into a nuclear reactor

The Ford Nuclear Reactor was built in 1955 to research the effects of nuclear power and peaceful uses, like using radiation in medicine. Operations ran until 2003, when it was decommissioned. The 13,200-square-foot building got a second life in 2015, when it was renovated into meeting rooms, offices and laboratories.

A few miles away near downtown Ann Arbor, engineering students can throw on their VR goggles and peer into the building’s history to test their skills. So far, the replicated nuclear plant only includes a few control rooms that were adjacent to the reactor. In addition to staring up at the reactor, which was recreated from the original blueprints, students can run different experiments — without the risk of nuclear contamination or worse.

The headset feels foreign at first. Weighing about a pound, it’s secured like a baseball cap with an adjustable knob in the back. Adjusting the eyepiece blocks out peripheral vision, and needs fiddling so the graphics aren’t blurry and that the apparatus doesn’t slip off your face. And then you need to adjust to maneuvering in the virtual world — i.e., resist the urge to walk around physically and instead get comfortable with the joysticks and buttons on two handheld controllers.

Starting an experiment feels more like starting a pop quiz. One shown to EdScoop involved placing an iron rod into the nuclear core. Students need to pick the correct specification — a 24-inch long, half-inch diameter piece — and then carry the sample over to the reactor core.

In a live reactor, the iron rod being inside the core for an hour would need to cool in the reactor’s surrounding water pool for five days. Michigan’s VR designers reduced those times to just a few minutes. The program exports data about the sample for analysis back in the real world.

“We wanted to recreate enough of the space that it feels like the real place, but keep it bounded to both keep scope limited and limit the places where the user can go, so that they stay focused,” Eric Schreffler, a Michigan XR developer, wrote in an email.

But those experiences also need to include the ability to fail, said Jacob Fortman, one of Michigan’s learning experience designers. And there are few environments with higher stakes than a nuclear reactor. Going through one of the virtual experiments incorrectly can trigger a SCRAM, or an emergency shutdown: The script ends, the reactor controls stop responding and the simulation resets.

Visualizing the impossible

Not every learning experience benefits from virtual reality, said Cat McAllester, senior director of engagement at Case Western Reserve University’s Interactive Commons, which hosts a full staff for developing and advising on immersive visual experiences.

Where designers see the most success is through specific applications within courses, McAllester said, Virtual reality and mixed reality are helpful in “visualizing the invisible or the impossible” and creating collaborative learning spaces where students can interact in these scenarios, she said.

Case Western Reserve University was an early adopter of HoloLens, a line of MR headsets from Microsoft, and worked with the nearby Cleveland Clinic to design anatomy software as a complement to introductory med-school classes.

Slicing open a cadaver is a staple for any aspiring doctor. But when a new medical student wields a scalpel, it’s easy for them to miss or cut through delicate nerve systems hidden within a mass of tissue, McAllester said. The anatomy program isn’t meant to replicate the experience of dissecting a cadaver, but is instead designed for students to comprehensively review anatomy of the human body at-scale. It also labels specific organs, veins, glands and nerves, similar to a printed textbook.

The HoloLens feels lighter than the Oculus, but it also doesn’t use a full eyepiece, as the users need to be able to see their real-life space.

A student wearing a HoloLens can stand behind a semi-translucent figure and line up their bones with a model of the skeleton so other students can see. After inspecting the skeleton, the instructor can move the program forward and the muscles layer over. The nerves previously hidden in gray-colored flesh in a cadaver are instead highlighted in bright colors.

And to see organ systems layer together — or just for fun — students can walk up and stick their head inside the model to see inside. A study on students who used the VR program compared to those who just dissected a cadaver found that the software cut preparation time for an exam from six hours down to three. That kind of time-savings is crucial for busy med students, McAllester said.

The Interactive Commons team is now working with other university departments to design immersive learning experiences using the HoloLens, and running “fellowships” for instructors to design new experiences.

Passing the fireball

But when none of it is real, how do you still give students a sense of community?

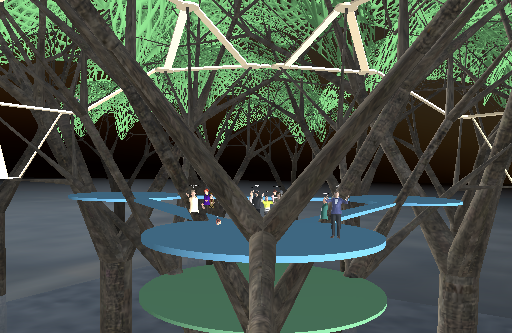

A course at the University of Miami is using virtual meeting spaces in a “metaverse” app called Engage to teach students how sacred spaces and architecture shape religions and communities. Twelve students studying arts, interactive media and architecture were lent Oculus headsets for the semester and met up for class in VR.

The course started off in one of Engage’s pre-built boardroom simulations. But instructors noticed that conversations were stilted, especially without the in-person routine of filing into the classroom and chatting before class. So the class swapped high-backed chairs for benches around a campfire.

“Everybody started talking, everybody relaxed. It was just stunning,” said Denis Hector, an associate professor of architecture. “Physically, we didn’t move, and the mood changed just as quickly.”

For their final project, students formed teams to design a virtual meeting space and communal rituals.

“We found out with the technology we couldn’t sing together, but we could move together and we could give things to one another,” said William Green, a Miami religion professor. “We discovered that there’s a haptic response — if my avatar touches somebody else’s avatar, you get a feeling in your hand controls, so there was that kind of connection.”

One ritual students developed had their avatars pass a fireball in a circle. Another involved being scattered onto islands, but not everyone took kindly to that: Fed up with the separation, one student “conjured” a flying bleacher to scoop up his classmates.

“In order to use [new technologies] properly, you just can’t be all by yourself doing it,” Green said. “You need people from different fields and different ranges of interest to come together to make this stuff really work effectively.”

“[VR] needs to be woven into the institution’s mission, and adopted in a way that serves the institution’s mission,”

Mark mcCormack, senior director of analytics and research, Educause

Feeding off “positive energy”

Still, classroom users of augmented and virtual reality need to prove they can be core academic tools and not just gimmicks, Educause’s McCormack said.

“It needs to be woven into the institution’s mission, and adopted in a way that serves the institution’s mission,” he told EdScoop. “It needs to, in some ways, push us to rethink our curriculum and our learning goals for our students.”

A few miles from Case Western, Cleveland State University is inventorying its VR and AR efforts to get a better grasp on which classes are using VR and how much equipment is available. Nelson, the head of Michigan’s extended-reality program, went through a similar process when he started the effort in Ann Arbor.

Cleveland State design students uses a VR platform called a VisCube. The headset is even lighter than the Oculus or HoloLens, more similar to a pair of glasses. But to use it, users step onto a platform surrounded by three large screens. The person with the headset on sees the VR world, but so do the people watching it projected onto the screen. Students design digital apartments and then use the VR set-up to confirm the details, like figuring out where a window lets in the most light or how high a countertop should be.

While ongoing VR can help build internal support for broader implementation, it can also appeal to outside organizations offering money, technology and advice.

“If the initiative is responding to some pain point, that is felt by employers, be it in the industry, or in the government, nonprofit sector, then you already have a customer — for lack of a better word — a partner who will help take things to scale,” said Shilpa Kedar, the director of a Cleveland State initiative that advocates for advanced technology projects.

Despite some colleges committing millions of dollars and dozens of people to VR and AR teams, other programs emerge organically.

Francis Yoshimoto, an assistant professor of biochemistry at the University of Texas San Antonio, said he found an open application, developed at the University of Pittsburgh, that converts 3-D models of proteins into VR. Yoshimoto showcased the program using a few headsets and help of staff from UT San Antonio’s technology lab.

After seeing his students’ “oohs” and “wows” as they zipped around the virtualized proteins, Yashimoto is now planning other lessons, like visualizing how the body metabolizes drugs.

“You feed off of that positive energy and it makes you happier to have this job,” he said.